Meme Commodities

Copper Edition

Following secular themes can be a good way to make money - if you read Marc Andreesen’s original “software eating the world” piece and bought a lot of large capitalization software and services names you probably did well and for quite a number of years. Much of that performance could be explained by the factor bets embedded in buying FANG and SaaS companies, and in a post Joachim Klement pointed out the large factor bets embedded in most thematic ETFs: mostly glamour stocks with mostly high valuation ratios and high revenue revisions.

Thematic investing occasionally spills over into commodities. Sometimes a big picture technology change or shift like “electric cars” or “shale” lead to a large number of investors piling in or out of a product exposure - long or short - with decidedly mixed results. There have been successful waves of this including people who saw the battery and lithium boom early on and also those who saw the disruptive impact of shale on oil pricing dynamics and how it would apply severe pressure on US coal fired power and related assets. There have also been recent mishaps including the crowded positioning in copper around a longer term EV and renewables thematic or investors in lithium during a China EV policy induced bear market and supply shock from early 2018 to mid 2020. The problem with this strategy is that commodities are volatile and the customer does not care about long term prospects: they want to buy metal or rock, turn it into something and sell it for a spread and the product is completely undifferentiated. Strategic stockpiling is remarkably rare and most people in the supply chain buy something today they will put on a boat and sell less than 90 days later. The long term is not the business they are in and substitution is high. The slow rate of being able to make more stuff means that most of the volatility is not in volumes but in price and margins.

An astute reader might point out that “that short term orientation does not apply to large capitalization mining companies” but, sadly, it does. Most investing appears to be pro cyclical because the value of the companies move with spot prices as do analyst estimates. Being contrarian in commodities is hard: maybe you are right, but can you stay funded and survive? The relative decline of commodity oriented private equity due to down cycles in commodities like oil being long enough to put both the businesses and the financial sponsors out of business is a profound challenge here. A telling example from the lithium cycle is Alita Resources which failed due to defaults on their off takes, went into bankruptcy and is still stuck there with a Chinese state linked buyer that cannot close the transaction due to FIRB rules and an administrator / liquidator who will not open up the transaction to competition for reasons unknown. At the time it failed with US$40mm in debt and was producing 80,000 tpa of spodumene fetching under $400 per tonne or well into the first quartile of the cash cost curve. To put it simply: it fell over when barely any company in the space was making money with not much debt - normally a good “loan to own” scenario. Lithium now now trades for over $6000 according to a recent auction. At the time value investors were nowhere to be found, nor strategics like Galaxy Resources which had a mine nearby. The cycle is brutal and heroes tend to be hard to find at the bottom. To try to tease out grinding structural trends in this kind of volatility is a choice, and in my honest opinion not a high risk adjusted return one. Investors who are not taking mid term market balance considerations to mind tend not to last.

Copper

Recent misadventures in copper are very much a case in point here. There are a lot of reports from investment banks indicating a bright future for copper demand: increased renewable energy needing more copper cabling, electric motors needing wound copper wire to make electric motors, batteries needing copper foil - the list goes on. These are often passed off by commodities research teams without much push back - so here are some of mine:

Batteries: What about flow based chemistries for bulk power storage on the grid? What if vanadium flow, new thermal storage technologies and industrial heat process technologies take a significant share here? What about pumped hydro which uses very little copper at all?

Power lines: The assumption here is that solar and wind are produced in remote locations and require extensive cabling. That is plausible for wind but for solar what happens if a lot of incremental build is on existing buildings or in smaller projects close to customers? There are a lot of tonnes in projections for this and not a lot of clear assumptions about what is required especially if renewables are integrated with storage to better utilize line capacity.

Electric Motors: motor design has a huge impact on copper requirements - there are sharp tradeoffs between rare earth consumption and copper consumption. The most bullish estimates for both cannot be right according to this presentation by IDTechx.

Projections nonetheless still look good - there is an incremental 30kg of copper in an EV versus an ICE vehicle and if you assume we get to 50 million EV sales in 7 years or so, that is a lot of copper even if you assume reductions in foil thickness and various other innovations. A long and thorough analysis can be found here but half a kilogram of copper per kWh is about right for now.

All well and good, but where is demand today? For the United States the answer remains building (~45%), electronics and cars.

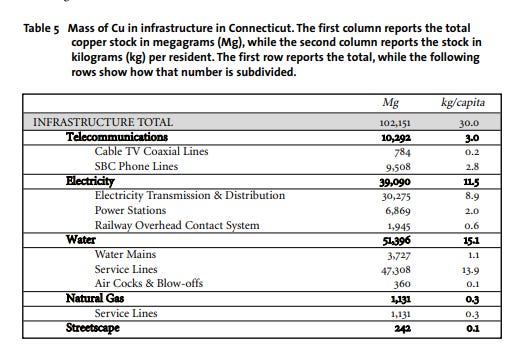

An excellent paper did a full inventory of the copper in use in Conneticut and came up with an even more detailed breakdown. While this paper is old (2007) it shows just how much of the copper is tied up in things that happen around new home construction: wiring, plumbing and installation of air conditioners.

These estimates may now be high. PEX piping is replacing copper in most plumbing systems, CAT 5 cable is being replaced by fiber cabling and airconditioners use a mix of copper and aluminum and have been reducing copper intensity for years.

For transport intensity is already high and tied to auto ownership - though this will go up with electrification.

Home appliances are big but once again like for buildings the most intense uses are heat exchanges like washing machines, refrigerators and air conditioners. For manufacturing while not broken out here the story is the same: anything that uses process heating or cooling requires copper.

And finally in the infrastructure category we have electricity transmission and distribution and some applications that are disappearing fast like phone lines, coaxial TV cables and the like that will soon be returned as copper scrap.

In total, this study shows what copper demand has been driven by: urbanization and penetration of appliance ownership. EVs will matter but as an impact on supply and demand they pale in comparison to the fits and starts of Chinese real estate and grid capital expenditure and to a lesser extent housing construction in the US and Europe. Chinese building completions - the time when the wiring goes in and people put in their appliances - are collapsing. This is not the the time to be long an industrial metal heavily exposed to building completions when it is at the top of the cost curve with no supply response likely anytime soon. For a long time China was riding an adoption curve for these appliances but now it appears to ebb and flow with real estate.

This ties with the Euromonitor data showing that air conditioning and refrigeration are now more or less fully penetrated and are going to show much slower growth.

For copper this is an even bigger problem: as anyone who owns an air conditioner in the tropics knows (me) an air conditioner does not last forever but the recycling rates are high. China will continue to use more and more post consumer scrap putting more and more pressure on copper imports over time. Electric cars might well offset most of this in a few years but extrapolating prior growth would be unwise.

If you wanted to construct a better model of prices you might:

Look at lead and lag relationships with building starts in China and elsewhere

EV sales

Appliance sales data especially air conditioners and refrigerators

General industrial and manufacturing capex

Where prices are in terms of cash costs and to what extent miners are investing in new output

(really clever) tracking scrapping rates and how much consumer scrap displaces newly mined copper

At the current time China completions are down and not bouncing much, EV sales are strong but not large enough and appliance sales having been massively pulled forward by COVID are languishing and unlikely to speed up due to market penetration. Industrial capex is good for now but could decline and heat pumps, while a great structural tailwind are not going to fill the gap anytime soon. It is not wholly surprising that in a major downturn in Chinese real estate copper prices might be weaker and with the the spectacular ramp in US mortgage rates that might continue for a time.

Commodities do have measures of how cheap or rich they are based on value, but those measures predictive value depends heavily on how readily you can arbitrage time: as we saw in March and April 2020, oil can trade for less than zero if there is nowhere to put it. Copper is more like a financial asset - higher value, easy to store and no doubt “value investors” will appear at some point. They will likely bring detailed supply and demand estimates and the cost of that production into their thinking and not Cathie Wood thematic approaches. They do this not for ideological reasons but because that seems to be what works.

"Lithium now now trades at $6000 ..."

I guess you meant lithium ore (spodumene), right? And maybe you could also mention the insane prices in 2022 for lithium carbonate, which would be more to the point when discussing margin for lithium. Cheers, Anon.

Hi Alex, thoughtful piece that is counter consensus. What about the supply side, increasing geopolitical risk and taxation, higher input costs, resource decline and a shortfall in exploration capex (let alone development capex) projected over the next few years. Understand (and agree) with the spot correlation and temporal dynamic…what are your thoughts on the supply side?