Rectification Campaign to Energy Crunch

How Chinese politics is leading to a chilly winter in Europe

Energy markets are a hot topic now with gas prices going vertical in Europe and coal prices breaking all time highs. There have been numerous hypotheses lodged online blaming some very plausible causes including reduced gas storage and nuclear and some where the causal link appears to be missing, like renewables. Renewables are variable, but without them Europe would undoubtedly need more gas and be in more strife.

Over the last year I’ve been working on a project with ANU on China’s coal markets and logistics and how domestic drivers lead to massive changes in imports. This focus has perhaps given me a different lens to look through recent energy market developments that I will briefly present here.

China’s energy markets and global markets, especially for LNG and pipeline gas have become increasingly integrated over the last five years.

For gas producers this has been a boon - a major new customer with strong growth while European demand has broadly been declining to flat over the period. It also means that what happens in China’s domestic energy markets does not often stay in China’s energy markets but is propagated throughout the world. As China has shortages or surpluses of gas, coal or electricity they spread rapidly across the world as China is a major and volatile importer of these commodities. To that end, understanding China’s domestic energy demand and markets and the dynamics of its most dominant fuel - coal - seemed worth the time as a research exercise as unglamorous and “dead” coal was in the public imagination.

By mid to late 2020, coal was looking to be in serious trouble. Chinese inventories were high and shipping data showed that much of the supply of coal to southern China was now coming from Northern China ports squeezing leaving little room for thermal coal imports and not just from Australia which was singled out for special treatment. Then something strange happened.

From early 2021 China started to draw its coal inventories down hard and deliveries from Northern Ports to Southern ports started to drop (red arrow above). This might not be a big deal, but China’s power demand was flying at the time with electricity consumption up ~14% yoy in April-June and steel output up 21%. Coal stocks started to decline rapidly as can be seen below.

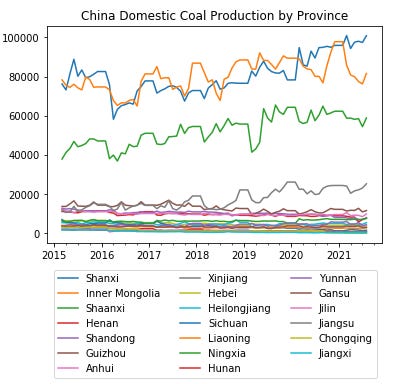

So demand was very strong but supply fell behind sharply both for domestic production and imports. China’s coal production is heavily concentrated in a few provinces as you can see below:

Over this period Inner Mongolia and Shaanxi output was poor - especially in the context of surging electricity consumption driven by industrial output of metals.

Imports were also weak from two major suppliers: Australia for political reasons, and Mongolia ostensibly for COVID reasons.

There is however another possible reason. During this period there was something of an anticorruption crackdown in Inner Mongolia which borders Mongolia. Decisions on mine approvals and the like are invariably contentious, especially during a period where the government is talking about greening the economy and commodity imports are often a source of graft. This article in Guancha may provide the answer.

学史,为明理、为增信、为崇德、为力行,一切的源泉是为了人民。审议临近结束时,习近平总书记语重心长讲了一番话:

“这两天,我看到中共内蒙古自治区委员会给党中央的一个报告,就是《关于开展煤炭资源领域违规违法问题专项整治情况的报告》。内蒙古在反腐败方面有个很重要的领域,就是煤炭领域。当共产党的官,当人民的公仆,拿着国家资源去搞行贿受贿、去搞权钱交易,这个账总是要算的。”

You can run that via google translate, but circa March of this year Xi was making explicit reference to anticorruption measures around the coal sector in Inner Mongolia. The collapse in imports and production over this period likely led to a shortage of approximately 30MT attributable to lost production and another 12MT from Mongolian imports. If you look at global seaborne coal imports, that is about two months of global imports, including China.

In gas equivalent terms, we know China takes about 330kg of coal per MWh of power, and a Combined Cycle Gas Turbine uses around 7GJ of gas per MWh. All in you are looking at bump in LNG demand to fill this hole equal to 5% of *annual* gas demand in Europe per IEA data.

What can or should we take away from this?

Firstly that global energy markets are tightly coupled now via fossil fuels. Expansions in LNG infrastructure and pipelines mean that regional prices should, in general be more tightly correlated.

European gas demand is falling but varies with renewable generation and weather. More storage of gas but also pumped hydro and nuclear will be required.

China is so big that seemingly obscure provincial corruption crackdowns in key areas can roil energy markets.

China does not seem to be stepping back from mass campaigns and the like any time soon.

The cost of fossil fuels is not just emissions but also in exposure to this volatility - if the energy transition seems expensive, remember that heating your home this winter in Northern Europe means you are paying a premium for China’s institutional and political volatility.