A recent Atlantic Council piece suggested there is something odd about where China is building its solar. On a simplistic level this is true: building solar in Shanghai where the number of hours of sun in the range of 1100-1400 hours per year is not as economic in terms of levelized cost or energy or LCOE as building it in Inner Mongolia where the number of sun hours is double that. So far so good.

The problem is, Inner Mongolia does not have the population nor the power demand. China has been trying to remedy this over the years by pushing more heavy industry inland to Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang - putting the demand where the cheap power is, both coal-fired and renewable. Nonetheless, more people live in the East and increasingly these people have air conditioning which means you either need to build staggering amounts of transmission to the East at high cost which China is doing and have a functioning national power market that can utilize that transmission with which China has less success thus far. This is improving and more a matter of market design and incentives which can be fixed much faster than building the power lines in the first place.

Another option if solar is cheap enough is to just put it where the people are. Happily, solar has only gotten cheaper and even assuming average prices on grid it is very competitive with coal now. However, I think the comparison to coal is a misleading one because solar is variable and when it produces and how that interacts with seasonality of power demand matters a great deal.

Look at the example of Guangzhou. Firstly, you can back out the seasonality of cooling and heating demand from renewables.ninja and what is clear is that there is strong seasonal cooling demand in summer and not much in winter - nothing new for anyone who has lived in Hong Kong.

Now using the Global Solar Atlas you can model a 10kw residential solar system and see how many hours of use you get by time of day and by month:

The peak solar output months match the peak air conditioning demand months. This makes it much less likely that a large amount of distributed solar would destabilize the grid or lead to seasonal excess supply. Drilling down to a daily resolution using a weather API you can see that cooling degree days (a measure of air conditioning demand) and cloud cover are inversely correlated in summer months: when there is a lot of unobstructed sun Guangzhou is hotter but this is also when the solar would work best. This is great and makes it seem very likely that policy makers facing a warmer climate and higher air conditioning loads will lean into distributed solar very hard in Southern and Eastern China.

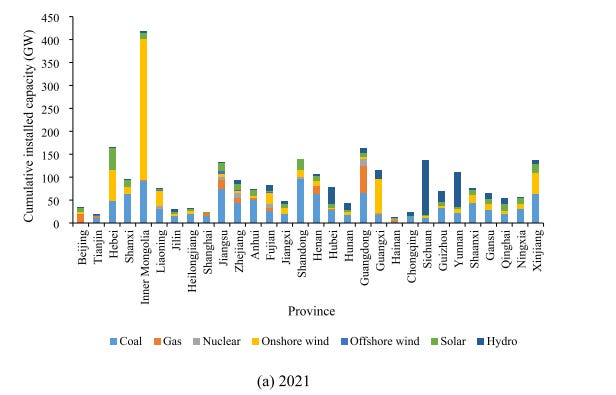

So solar in China’s coastal regions works well because it correlates well to actual demand. The question of course is who loses out on this development? To understand that we need to look at the grid as it is today and for this I am going to lean very heavily on a publication by CREA produced by Water Rock called “Resolving near-term power shortages in China from an economic perspective”. A standard load curve is produced in their report which is below:

The loser is gas - and in particular LNG imports for power burn.

It is incredibly difficult to track China’s distributed solar output - there are official figures for installed capacity above 6MW output but nothing below that. You have to guess - though educated guessing using location and plant sizing and design data is possible combined with weather data albeit difficult. What we can get some broad estimates of is Guangdong’s power mix assuming this level of torrid solar and wind build out continues. Using very sane assumptions I get to thermal demand dropping ~50% to 2028 - even more if you assume solar ramps even harder. This also assumes 4% demand growth which is probably heroic in a country that has largely built consent around a peak in steel capacity and a structural slowdown in real estate.

You could run a similar analysis for different coastal provinces and if you are in energy or LNG trading you probably should because this is where the power burn is.

For coal producers this is similarly not great.

If you are in the national security field then it needs to be seen as an assumption that China is moving towards energy independence in provinces that depend on shipping - speed may vary depending upon growth and hydropower but the trend is very clear.

At this point you might note the rise in coal imports the last few years and to that I will say - let me talk about the China and global hydro cycle in the next piece.