A Reply to Zoltan Pozsar

Bretton Woods III or just new trade network topology?

First off - I am a big Zoltan fan and enjoy his writings about rates markets which, if I try a little and drink some coffee, I can mostly understand. That being said, I think his most recent piece on what is happening in commodities markets is off the mark in parts.

First — the good. The below is manifestly true:

First, non-Russian commodities are more expensive due to the sanctions-driven supply shock that basically took Russian commodities “offline”. If you are a (leveraged) commodities trader, you need to borrow more from banks to buy commodities to move and sell them. Second, if you are long non-Russian commodities and short the related futures, you are likely having margin calls that need to be funded.

This is showing up in the cash bond prices of commodity traders like Trafigura and portends nothing good.

Companies like Trafigura would have OTC off takes with Russian producers which are hedged with futures. Now it is unclear if they can take delivery of that oil anymore or if they can settle the trades and in the meantime their short futures position is exploding upwards requiring margin to be posted. Not good.

Zoltan is also correct in noting this never comes up in financial stability reports, but perhaps more damning it does not come up in the academic literature either. The difference between money and commodities is that money is “mind” as a Tibetan Buddhist might say - if you share the “mental formations” or “concepts” of what is money, you can trade it with people on that shared understanding. It is a shared idea first and foremost and institutions around it which means that if a central bank decides that Greek bonds are now “money enough” they really are! Amazing. Monetary economics is something akin to purity in many religions: if the priest or brahmin says so, it really is so - appeals to authority work and are not falsifiable.

Commodities are not like that. They exist and move through physical space: the plumbing is actually plumbing, something that the academic literature has oddly forgotten - outside of power markets. Power markets often face extraordinary volatility due to weather driving both demand and supply especially so with growing renewable output. To that end the literature in power markets as well as day to day practice at grid regulators is heavily focused on scenario testing for flow constraints, potential outages of transmission leading to localized shortages and how best to ensure reliable supply at reasonable cost. That sounds a lot like the world we find ourselves in today: commodities do not just clear in an abstract market at a few sites that qualify for futures delivery with perfectly fungible (but not free) transport anymore. Markets now are much like power where if a transmission line goes down you can have feast on one side of the line and famine on the other.

This might sound obvious now but even in the academic literature there is nothing on google scholar which models network flow in oil or gas internationally, and nothing which ponders the impacts of sanctions and how flows might adjust to get around them.

Nor is there anything as to how there might be trade offs between cost and speed of an energy transition and exposure to these kinds of shocks - do you stockpile oil, or push EV incentives harder, for example. Suffice to say outside of people who wrote about European gas vulnerabilities there has been limited work done to answer the questions we have right now. A starting line would be to build good network models for all the infrastructure, preferably open source. I am a co-author on a paper like this for coal but we desperately need it for oil and gas right now.

Back to Zoltan’s piece - this relational element and logistical element is nowhere in his analysis. Trafigura might not be able to trade with some parties now, but can with others and a Chinese entity set up to trade with Russia might be able to trade with Russia, but not others nor have access to SWIFT. Then, one layer deeper, some shipping companies might be able to trade with some and not others. If this all sounds a little like exclusive dealing and vertical networks in the railroad baron era that is because this is exactly what is happening - the system now has a lot more constraints and a lot more non linearities. One of the big losers in all of this is likely to be freight shipping: as China is likely to trade more with Russia the appeal of overland transport is going to be significant here both to avoid detection and ensure capacity. Similarly, it would be remiss of China to not build more liquids and gas pipelines as quickly as possible. I think Zoltan’s trade recommendation on shipping names is poorly considered.

How will companies and countries hedge their forward consumption? Quite clearly post the action on Russian reserves money does not hold the same appeal it once did. Countries could produce more commodities domestically but that is unlikely to be required for things that are highly priced in terms of weight: that stuff tends to leak out regardless - google “Congo conflict minerals” for more. If Russian nickel doesn’t miraculously make its way to China I will be very, very surprised. For coal, oil and gas hedging can both be via production of the commodity (“drill baby drill”) or finding another way to do the job of the commodity which leaves less exposure to messy value chains. Alternative energy sources and storage are the answer here. The truth of the matter is that the Buddhist term of dukkha or “suffering” but better translated as “the grind” applies well here. Commodity supply chains are ever present and gritty things but whether you are a individual buying an ebike or a country rolling out renewable energy you can attenuate that suffering by rethinking in terms of things you actually consume like heat and light and not be stuck in concepts like coal, oil and gas. The path that frees you from suffering “magga” is in decoupling energy from fuels, consumption from energy, and perhaps at a more fundamentally Buddhist level, happiness from consumption. The latter is a big ask but the first two are worthy policy objectives. To that end it is quite bizarre that Zoltan has nothing to say about alternative energy investments as savings for future consumption.

Zoltan’s solution - that the PBOC be a kind of grand commodity backstop misses the point that the problem is not money - it is logistics. No doubt some enterprising people in China — perhaps a man called Ma-ke Rui-she — will work out how best to optimize freight flow along the Trans-Siberian railway, sort out a truck fleet, perhaps build a few private pipelines and be very wealthy. He may never have a Visa card or take his kids to Disneyland, but I suspect that is not going to bother him too much. That will allow a certain amount of product to flow out from Russia to China and coalesce into stronger trading bonds between the two while perhaps Australia ships LNG to Europe. Global balances will clear but it will take some scrambling and the mess we see today is indicative of that.

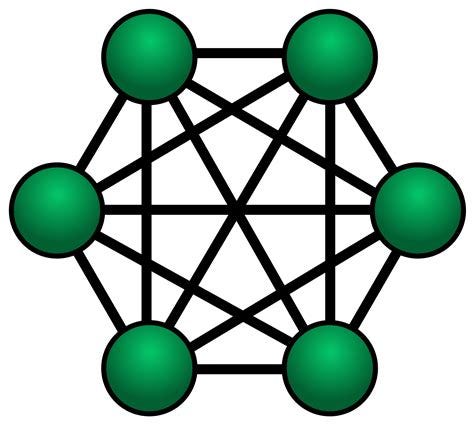

What does this look like in a year? Trade will look less like a fully connected network where everyone trades with everyone. Instead, there will be two clusters with some parties that trade between both networks perhaps via intermediaries, perhaps covertly but a great many who do not. Medium term the network flow is likely to go backwards sharply as Europe and other places decarbonize in turn leaving less scope for shocks in inflation and growth. I don’t see any likelihood of “commodity money” making a comeback here: if you want to opt out of this shock, buy an EV, an ebike, put solar on your house and get a heat pump. Much unlike the 1970s you don’t have to live in the woods Unabomber style to opt out of this which is why I expect demand response and some normalization will be swift.

Will the accelerated demise of fossil capitalism and its web of interconnection be a bad thing? In my opinion, no it will not because the planet and the systems that support life will have much better odds. There will be less trade offs between values and interests which likely means less “Londongrad”. So far so good. However there could also could leave more scope for the two emerging energy blocks to pursue “unfinished business” without as sharp economic costs. I worry that world with much less energy commodities might be cleaner, but also more violent.

Your rebuttal seems to be looking at an entirely different timeframe than Zoltan's Hypothesis as it concerns commodities and shipping. You state "One of the big losers in all of this is likely to be freight shipping: as China is likely to trade more with Russia the appeal of overland transport is going to be significant here both to avoid detection and ensure capacity." While a sensible conclusion, this infrastructure does not currently exist.

Building pipelines not yet announced is a decade long project. The latest Power of Siberia Pipeline, announced in 2007 first shipped gas in 2019 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_of_Siberia. Even PoS2 is fast tracked we are looking at 5+ years as a best case scenario.

Capacity on trucks and trains to move oil, coal, iron ore, bauxite is basically immaterial and ridiculously cost prohibitive unless the cost of ocean shipping triples. Therefore, even if the Zoltan thesis of commodity storage on ships does not play out, ocean freight rates are likely to surge due higher utilization of the existing fleet for long haul Black Sea and Baltic trade to China that would otherwise go short haul to Europe. Should ocean freight triple with no relief in sight, only THEN might it make sense to add rail capacity. I find this HIGHLY unlikely as it is still far cheaper to just build more ships - something China is very good at.

To sum up: trade dislocation with longer sailing distance will overwhelm finely balanced ship supply and demand sending freight rates much higher. Overland relief is immaterial and uneconomic outside of oil and gas pipelines which will take 5+ years to build. The economic solution is to build more ships but ship orderbooks for drybulk and tankers are at all time lows as a % of fleet and shipyards are full Through 2024 end. IF Russian commodities do end up going to Asia instead of the west, the world is structurally short on ship capacity until at least 2025, likely longer.

As someone who considers their expertise to lie in ocean freight, I would say Zoltan is spot on for the medium term about high ocean freight rates (~5 years) and any marginal pipeline capacity initiated due to recent events will take 5+ years to be built and have an impact which will be anticipated far in advance by new ship capital spending plans. There is still no sensible alternative for drybulk cargoes. The only scenario in which ocean shipping 'loses' as you suggest is if commodity shipments from Russia are curtailed, otherwise the trade dislocation is a huge boon for shipping as Zoltan suggests.

Where is the source of Zoltan Pozsar, that you are responsing?